WINE REBELS: MAKING WINE WITHOUT PERMISSION

Photo of Sean O'Callaghan of Tenuta di Carleone in Radda Chianti Classico

Written by Kendall Holmes, Kevin Hart & The Cru

At Hart & Cru, we don’t look for rebellion just to be edgy. We seek rule-breaking that tells a more compelling story and reveals a deeper truth. Some of our favorite wines arise from the tension between following rules and breaking them in ways that elevate the varietal and illuminate culture.

Wine Rebels

Every society imposes order through rules. In religion, finance, and economics, rules are usually crafted with good intentions. But times change, and rules can hold us back. That same tension plays out in wine, where convention and innovation clash.

Winemaking is both cultural and deeply personal. When passion leads a winemaker to contradict regional regulations, they often forfeit the right to list the region on the label. In much of Europe, that means settling for the 'table wine' designation, a category with little prestige.

Despite that, many winemakers embrace table wine status to maintain integrity. Cracking open a bottle labeled Vin de France or IGT can be like discovering a geode: the beauty lies within.

At Hart & Cru, we love those wines. They tell a deeper story of land, legacy, and defiance.

Rules, Rules, Rules

There weren’t always so many rules in European winemaking. Many regulations began as traditions written into law, shaped by politics more than terroir.

As Jon Bonné writes in The New French Wine, the institutional structure of French wine emerged after war and economic collapse. Phylloxera had devastated vineyards, and the two World Wars hollowed out the countryside. What followed was instability, fraud, and confusion. Rules were introduced to restore order and bring trust back to the bottle. Over time, however, those protective boundaries hardened. Innovation was stifled, tradition was frozen, and entire generations of winemakers were told to color inside the lines. Eventually, those lines became borders, and borders became battlegrounds over what wine should be, rather than what it could be.

France: AOC (Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée)

France’s AOC system, created in the early 20th century to combat fraud, now dictates nearly every aspect of production. What started as protection has become restriction.

One such law dictates that producers must only use sanctioned grape varieties in designated regions. That means innovative blends or unconventional varietals disqualify the wine from using its geographic name.

Laurent Vaillé of La Grange des Pères opted out of AOC constraints, blending grapes and techniques learned from legends like Coche-Dury and Chave. His wines became cult icons not because he followed the rules, but because he knew when to ignore them.

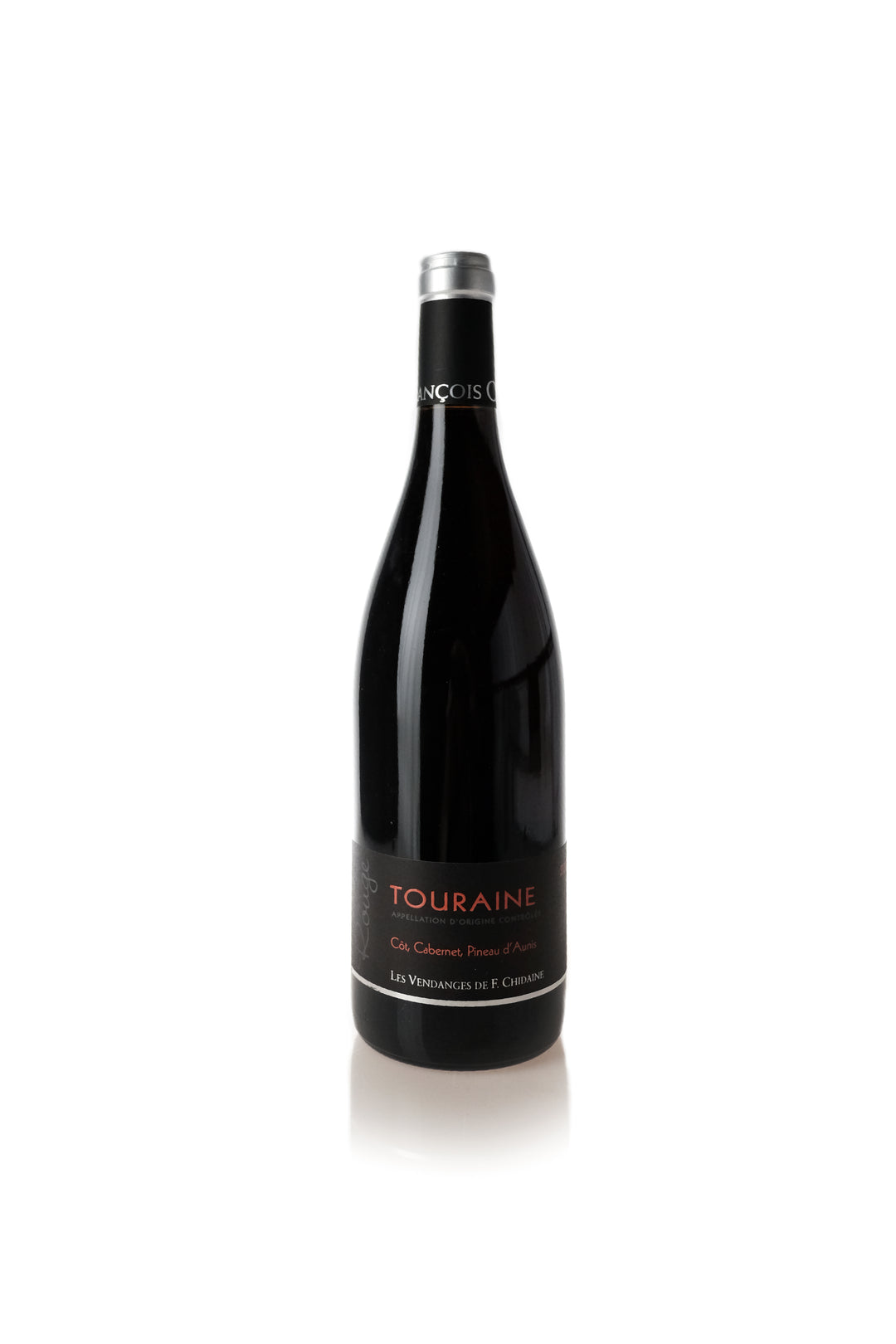

François Chidaine, based in Montlouis, has pushed back against the influence of wealthier Vouvray, whose sway over wine laws has marginalized neighboring villages. Rumors persist that Vouvray has even paid to keep Montlouis off tourist maps. Chidaine refuses to compromise, and his wines speak for themselves. He earns acclaim while defying a system that favors politics over quality.

Italy: DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita)

Italy’s DOCG rules define grapes, yields, and techniques, but struggle to keep pace with regional diversity.

A key law once mandated that Chianti Classico wines include a blend of Trebbiano, even when many producers believed it diluted the wine’s quality.

Sergio Manetti of Montevertine dropped out of Chianti Classico in 1981 rather than blend in Trebbiano. Labeled IGT, his wines now command premium prices.

The Super Tuscan movement was born from defiance. So is Sean O’Callaghan’s work at Carleone.

Sean O’Callaghan of Tenuta di Carleone said it best: “I was given a clean slate to do what I like and more importantly what we would like to drink.”

He rejects over-extracted Sangiovese in favor of elegance. Many of his wines bear only the Toscana IGT label, even though they qualify for DOCG. His style is atypical, driven by passion, not performance. The wines reflect his personal vision and the possibility of detail and quality outside DOCG expectations.

Spain: DO (Denominación de Origen)

Spain’s DO system is one of the most layered in Europe. Regional councils dictate varietals, yields, and aging categories.

Among the most controversial rules is the Crianza/Reserva/Gran Reserva structure, which classifies wines by barrel aging rather than site quality or vineyard specificity.

Pepe Raventós left DO Cava in frustration over lax quality control. He created Conca de l'Anoia to champion site-driven sparkling wine. He believed the large producers had diluted the standard and cheapened the image of cava worldwide. His decision sparked debate across Spain. “Every generation should start from scratch, following their dreams,” he said.

Daniel Landi of Commando G is taking a Burgundian approach—single-site Garnacha from the Sierra de Gredos. His focus on terroir and finesse challenges Spain’s aging-centric orthodoxy. “We’re opening the doors and windows,” he said. “The world is discovering what treasures the castle has inside.” By narrowing in on specific vineyard sites and their subtle differences, Landi is shifting the conversation in Spain toward detail and transparency.

Germany: VDP and Qualitätswein

Germany’s 1971 law ranks wines by sugar content, not vineyard. It’s outdated and out of step with the rise of dry, terroir-driven wines.

According to the law, higher must weight correlates to higher quality, leaving dry wines and experimental styles poorly recognized.

The VDP, a private association, created its own hierarchy based on site. But rebels still push further.

Ulli Stein plants Cabernet Sauvignon in the Mosel, one of Germany’s most sacred Riesling zones. He knowingly defies the regional varietal laws that forbid nontraditional grapes in designated vineyards. He did it to test the system, to challenge the idea that only sanctioned grapes belonged. His Rieslings are also rebellious—dry, mineral, and often outside the typical classification. “I think I'm now too old to let anyone forbid me anything,” he said.

His wines exist outside the system. And they’re better for it.

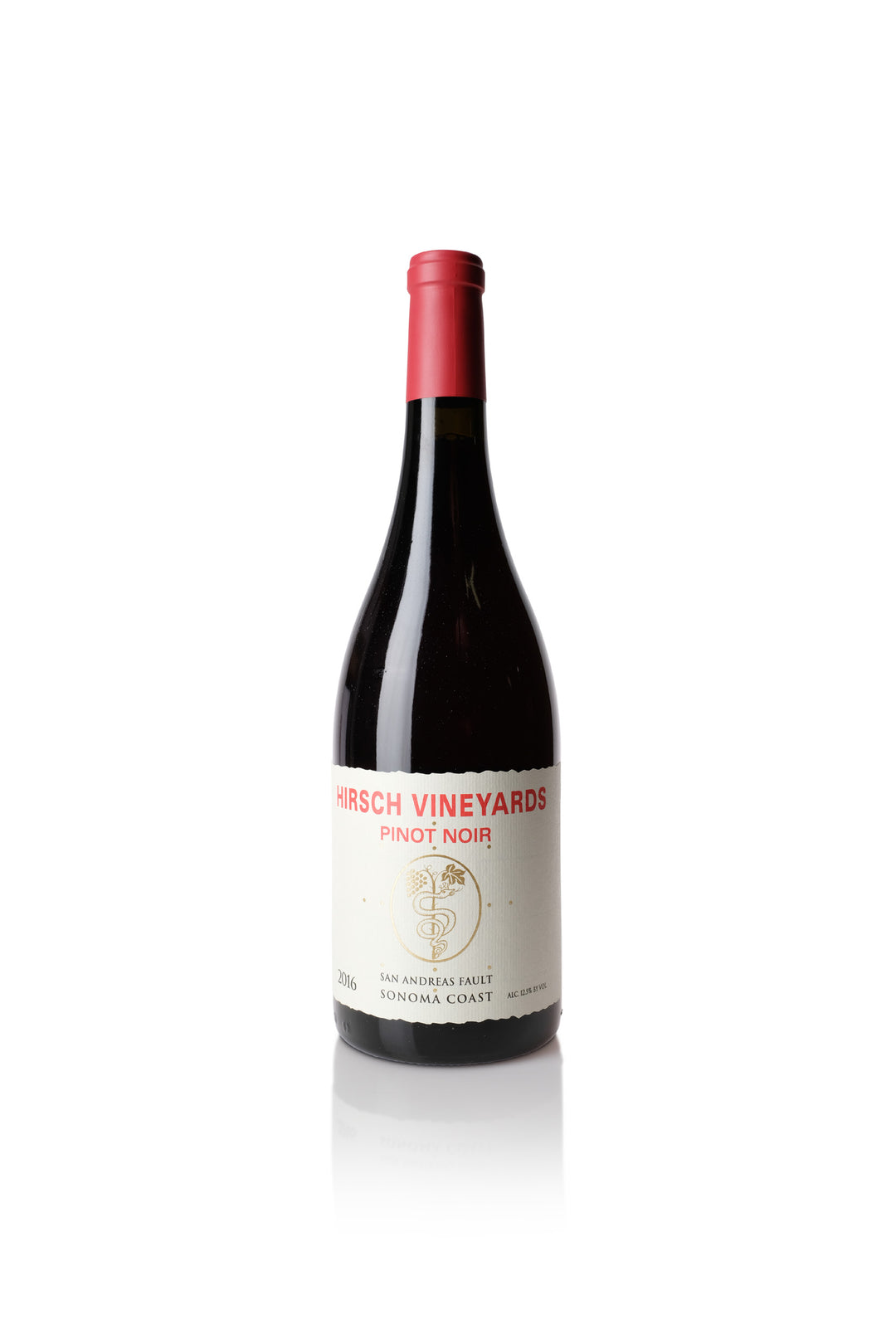

United States: AVA (American Viticultural Area)

The U.S. AVA system is minimalist. It defines geography but imposes few winemaking rules. This allows both creativity and inconsistency.

A key technical requirement is that 85 percent of grapes must come from the stated AVA and 75 percent of the varietal listed must be present. Oregon’s laws are even stricter.

This flexibility fosters innovation in regions like Texas, Michigan, and Sonoma.

Some winemakers skip AVAs entirely, focusing on narrative and philosophy.

Jasmine Hirsch’s father, David Hirsch of Hirsch Vineyards, planted Pinot Noir on the far Sonoma Coast when others said it was too cold. At the time, this move defied both industry expectations and informal norms about where quality Pinot could grow. Now, coastal Pinot is widely accepted, and Hirsch Vineyards is one of the most iconic sites in California. It's a powerful example of how one rule-breaker can shift an entire region for the better, even if it takes time. Jasmine reflects: “You have to be independent-minded, you have to be stubborn, you can't be afraid of hard work, and you have to believe in what you're doing.”

The Wines That Refuse to Ask Permission

These wines don’t just break the rules. They make you forget the rules ever mattered.

Sometimes, wine needs a little “fuck the police” energy.

Not rebels for the sake of it — but because the grape, the place, the moment demands more.The ones we love don’t ask if it’s allowed. They just do it. And the wine is better for it. Here’s to the winemakers who say yes when the rules say no.

Here’s to the wines that never ask permission.

SHOP WINEMAKERS MENTIONED ABOVE